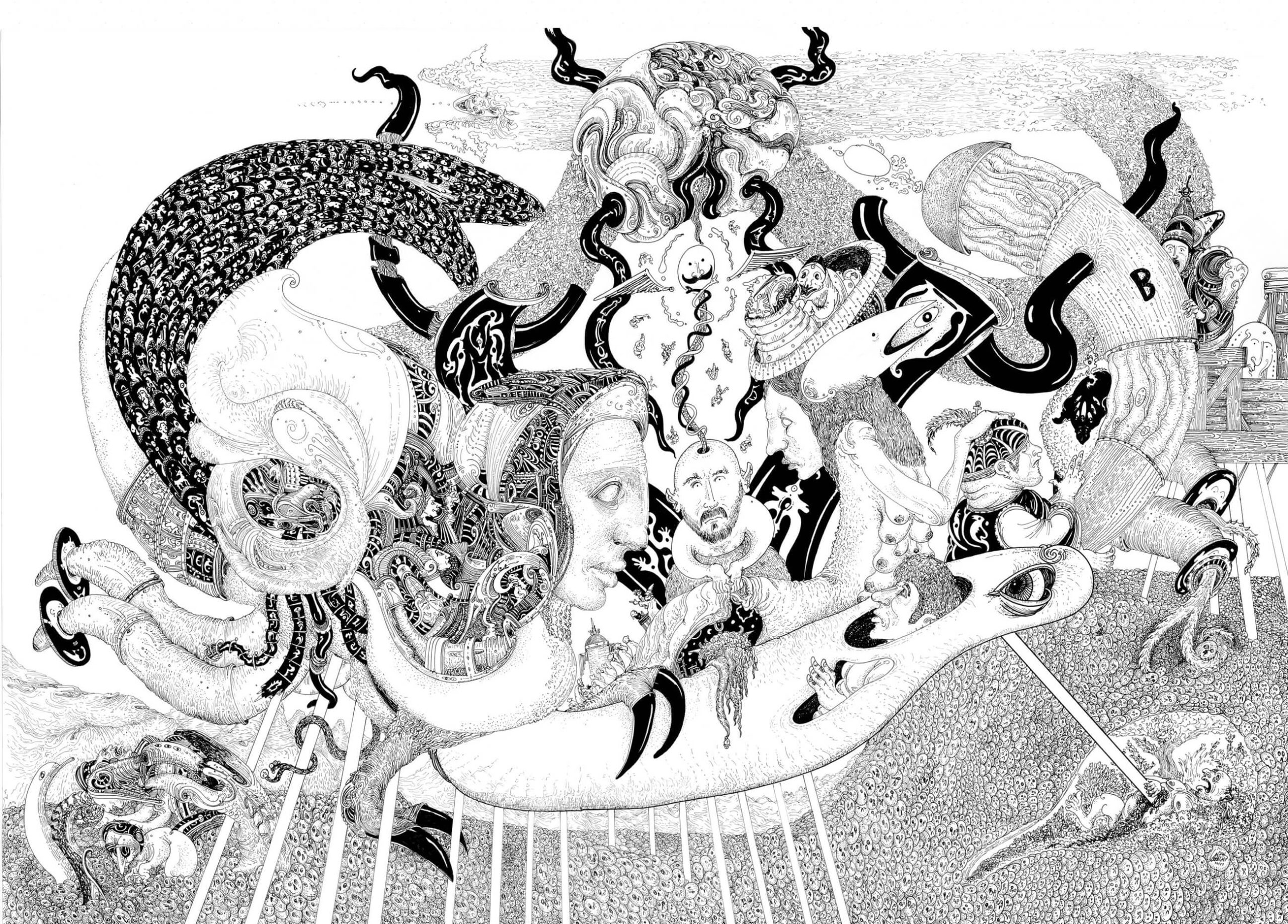

Article by Ilias Kasselas on his painting, as part of his participation in the “Ink On Paper” community.

The way I work can be briefly described as “automatic drawing with a marker on paper,” combined with a more conscious—perhaps traditional—approach to drawing and composition. This means that, for the most part, each work produced is the result of a truce between gestural freedom and deliberate artistic intent. Chaotic forms are filtered into structured depictions, while structured shapes suddenly become subject to irrational transformations—everything flows as it is meant to. I don’t stress about it: any piece that I feel does not breathe as I would like it to, I destroy—regardless of whether I’ve worked on it for minutes, hours, or even days.

As a student at the School of Fine Arts in Florina, I began painting years ago first with India ink and brushes, and later transitioned to markers—initially alongside ink, and eventually on their own. Two reasons led me to work with and eventually love ink in its various forms: the first is its immediacy, which stems from its unforgiving nature—in simple terms, you essentially can’t make mistakes when drawing with ink. The second reason is my long-standing admiration for painters and illustrators associated with or orbiting around the broader Art Nouveau movement in England during the 1800–1900s, such as Beardsley, Clarke, and above all, Austin Osman Spare. Spare had a defining influence on my early work—both stylistically through his paintings and in how I understand and use automatic writing, thanks to his books.

Automatic writing in painting, to me, is a technique that can be cultivated and used as a creative tool or source of inspiration. There are impressive examples of automatic writing among early 20th-century surrealists, but my focus is on the existential and esoteric approach of Spare. I studied and experimented with the few techniques derived from his work, and the culmination of my own experiments between 2012 and 2015 revealed two fundamental truths: first, beyond the common definition of reality, there is a field of information I can access by emptying the mind, creating images that belong to all of us. Second, repetition and habit can convince the mind of anything, if proper techniques and terminology are applied. These realizations shaped my artistic path. I continue to see automatic writing as a technique—regardless of mystical or egocentric connotations—and I am clear that any sense of mystery around it is exaggerated.

With a marker, one can leave three types of marks on paper: dots, lines, and curves. From these arise all the ways one can draw. Dots and lines, for example, can be used to depict the volume of an object—cross-hatching, for instance, uses repeated lines for this purpose. For some objects or surfaces, a specific approach or pattern may be used—like the “grain” of a wooden surface or the texture of an ancient white column.

In the past, I would allow automatic writing to take full control, and the final result carried the honesty of an unfiltered gesture and image. However, it often lacked in terms of composition, narrative, or even atmosphere. Over time, I’ve reached a point where I try to reconcile those two painting needs. If I have a 70 x 100 cm sheet, for example, I’ll begin with some loose pencil strokes—lines that start to suggest possible volumes. Then I try to approach the mental state in which automatic writing can thrive and begin drawing with a marker from a random spot on the paper, continuing until I feel I must stop. At some point, I’ll step back and observe what I’ve made, and consciously decide whether to follow a shape or pencil mark and turn it into “something.” Other times I’ll ignore the sketch entirely and do whatever I please. Inevitably, organic forms begin to emerge—bits of flesh, animalistic or human or almost-human figures. Sometimes I’ll draw them instantly, automatically with the marker; other times I’ll decide they’re worth a proper, anatomically correct sketch first, and only then apply the ink. These days, I’m more interested in the composition or inner architecture of a piece—in the balance (even through total chaos) of all the elements within it—rather than in each element separately.

My work as a drawing teacher for the past 10 years has helped me re-evaluate the importance of certain principles of academic drawing, always in relation to how they can serve what I want to produce. Some of these rules I consciously reverse. One simple example: in academic drawing, especially with charcoal, heavy closed outlines are forbidden. In what I produce—something more like fishing from a chaotic, constantly shifting imaginary reservoir—I regularly work with closed outlines; there’s no other way to trap the fleeting form and impression on my paper. Another example: a human figure is drawn using specific proportions, especially with regard to gender. I’m not always concerned with this—a human figure on my paper may transform at any moment into something bestial and obscene. Or into something exalted and precious—yet still not human.

Talking about the subject matter of your work can seem dull, especially when it involves Western esotericism and mysticism—concepts often seen as eccentric or incomprehensible. As an artist with a rational upbringing, I understand this view and try not to overwhelm my audience. However, my engagement with automatic writing and the exploration of mindscapes is deeply sincere. These experiments represent meaningful, living conclusions in my journey so far, and I treat them with seriousness and a sense of responsibility.

Visit Ilias Kasselas’ webpage

Visit the Ink On Paper community site